| Rather than reciting a timeline of personal history, this memoir portrays the family influences which have shaped my life and character. Before this life, the mission I chose for myself was to accelerate humanity’s conscious evolution through authorship of the first caliber. To support my pursuit of this lofty goal, I joined a family whose roots in publishing reach back to the late 19th Century. |

My great-grandmother, Josephine Turck Baker, established the International Society for Universal English in 1899, and founded the Correct English Publishing Company in Evanston, Illinois. She was a renowned author, speaker, composer, playwright, actress and tireless advocate for women’s suffrage and other liberal causes. Her elegant home at 1742 Asbury Avenue was the center of Evanston social life during the first three decades of the 1900’s.

My grandfather, F. Sherman Baker, grew up on this estate (as did my mother, Penelope). Josephine adored her son, and as a child, Sherman was indulged in his every wish. He received a Pope motorcycle on his 13th birthday, a new Ford on his 16th birthday, and a Stutz Bearcat for his 18th birthday.

My grandmother, Margaret Darlington, came from a Chicago banking family, and for her 18th birthday, she received a debutante ball which was covered extensively in the Chicago Tribune. (I can still remember her showing me the newspaper page which she had kept.) |

Josephine Turck Baker

Josephine Turck Baker |

Sherman Baker at Oxford

Sherman Baker at Oxford |

After graduating from college, Sherman Baker married Margaret Darlington, and the couple received a year in Europe as a wedding gift, which they extended to three years, living primarily in England and Italy. During this time, Sherman completed his postgraduate work at Oxford. When I first expressed literary ambitions at the age of 17, my grandfather gave me his writing textbooks from Oxford and began tutoring me in the craft of authorship.

After working in his mother’s publishing company, Mr. Baker and his family moved from Chicago to New York in the early forties where he joined Appleton-Century. He went on to become editor-in-chief of one of New York’s largest and finest publishing houses, St. Martin’s Press, where he was also vice president and a director.

The Baker family lived in a charming home in Hastings-on-Hudson built by Admiral Farragut in 1862. Dozens of champagne bottles were suspended on wires from rafters high in the kitchen ceiling, each commemorating a special occasion Sherman and Margaret had shared. |

Sherman and Margaret had three children, Priscilla, Frederick and Penelope. After Harvard, Frederick moved to California, but Priscilla had settled in East Hampton with an artist, Ted Griffin, and started a family. After years of visiting East Hampton, Sherman and Margaret fell under its spell, and in the sixties, they moved into a home on Egypt Lane, a short walk from the Maidstone Club.

The property had a quaint guest house where our family stayed whenever we visited, and a long backstretch leading to a nature preserve where my sister Margaret and I would go to feed the ducks. Priscilla’s sons, Mark and Steven, were natural athletes, and they taught me how to surf at nearby Georgica Beach and Ditch Plains. Their lessons paid great dividends when I lived in Southern California later on. |

After WWII, Penelope married a dashing Air Force Captain, Frank Mee, who was a hero in the European theater. Before going overseas, Capt. Mee was a flight instructor in Shreveport, Louisiana. The city has three bridges over the Red River, and several tall buildings which are situated close together. This layout apparently provided an ideal landscape for aerial fun and games. I have heard stories about my father taking his heavy bomber on daytime “training missions” and flying under the bridges and sideways in between the buildings downtown. I think they are probably true.

This was just the beginning. The countryside around Shreveport in the forties was dotted with cotton farms. When the crops were harvested, the cotton balls were temporarily stored in open aluminum cylindrical containers around 15 feet high. Apparently, when one dives a Martin B26 airplane at high speed and from sufficient altitude, pulling up at the last minute just before reaching one of these containers, the prop wash is powerful enough to send a flurry of thousands of cotton balls up into an aerial geyser. The same principle can evidently also tip over sailboats on Lake Ponchartrain...in theory, of course. (No one actually ever did this.) |

Flying over Louisiana in nighttime “training missions” (translation: joy rides), my Dad would spot drive-in theaters and approach them as if attempting to land in the parking lot. The heavy bomber would come barreling in over the movie screen with its wheels down and its landing lights blaring. This would cause a feeling of unease among the theater’s patrons, but the cars would generally stay put. After two or three passes, though, the drive-ins would usually clear out.

A few weeks after arriving in England, Capt. Mee caused a panic in his British air base. The B-26 airplane, which carried a crew of six, had an occasional tendency to lose its number two engine 90 seconds after takeoff, earning it nicknames like “widow maker” and “flying casket.” On his approach to the field one day, my father shut down the engines of his B-26 and coasted in for a power-off landing “just to see if he could do it.” The control tower spotted the powerless aircraft approaching and sounded the alarm. Fire trucks and Red Cross jeeps swarmed the field as the silent bomber glided in. They witnessed a perfect landing. Captain Mee was escorted to the base commander’s office to be chewed out, but the colonel’s tirade was only half-hearted. They both knew my father was one of the best pilots the Air Force had.

|

Capt. Frank E. Mee

Capt. Frank E. Mee |

My father taught me rugged self-reliance and strong determination, providing an invaluable counterpoint to the more ethereal Baker influences. He also taught me how to build things. Our house on the north shore of Long Island had a large, unattached garage, and in it, my father and I built a sailboat, which I often sailed in nearby Laurel Hollow. Larger sailing trips were taken out of Huntington harbor on Uncle Wally’s yacht, the Crescent Moon, which carried parents, children and dogs across many happy leagues of Long Island Sound.

I did not receive a Stutz Bearcat or a debutante ball for my 18th birthday. Instead, my father and grandfather took me to Brooks Brothers in Manhattan to be fitted, and then to Sherman’s club, The Players, which was near his office in the Flatiron Building. The club had beautiful artwork and chandeliers, overstuffed leather easy chairs, a library, a well-stocked bar, and men smoking cigars. Women were not allowed. |

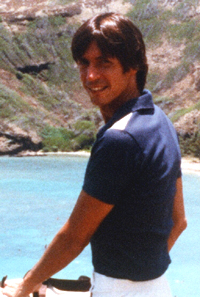

The Author at 32

The Author at 32 |

My father always supported my career ambitions. When I made the dean’s list at Wesleyan, he gave me a key to his club in Manhattan. When I started a laser printer company in my early twenties, he introduced me to his friend Pierre Rinfret on Wall Street, who was economic advisor to President Nixon. When we met with Mr. Rinfret, one of his analysts pointed out that if a laser printer was such a good idea, IBM would already have one. (They didn’t.) Mr. Rinfret’s firm did not invest in my company. A year later, IBM announced their laser printer. Shortly thereafter, IBM’s largest competitor hired me into product planning. I rose rapidly in this company (Honeywell) and became the youngest father of a mainframe computer at the age of 37.

My parents were avid entertainers, and hosted or attended parties with their friends almost every weekend over the span of four decades. They travelled extensively, and at their social zenith, they had friends in 20 states and 11 foreign countries. Despite the non-stop social whirlwind (or maybe because of it), they enjoyed perfect health.

As was the family tradition, our family had dinner by candlelight most evenings. The dinner table was the place where children learned the social graces and the art of conversation. Dinner was always preceded by The Cocktail Hour (when children may be seen, but not heard).

|

| Our summers were divided between East Hampton and the Adirondacks, where we would stay at Uncle Wally’s boyhood summer home, High Huddle, overlooking Trout Lake (near Lake George). A long driveway through the woods opened up to a big lodge with a dozen bedrooms, a boathouse, canoes, a guest house, a badminton court, an outdoor sleeping porch, and a winding trail leading down to a dock on the lake. The children always outnumbered the adults, and we favored the outdoor sleeping porch and the crisp, refreshing Adirondack night air. In the mornings, we would fill aluminum buckets with wild blueberries from the bushes outside the house and bring them into the kitchen where our mothers would make fresh blueberry pancakes. |

| In the summer of my 17th year, my parents sent me to Europe to broaden my cultural horizons. I used this golden opportunity to acquaint myself with alcoholic beverages (the legal drinking age was lower in Europe) and to do idiotic and sometimes perilous things. The pinnacle of stupidity came in Switzerland, when a friend and I decided on a whim that we could traverse the top of a massive glacier at the source of the Rhone River in Gletch, Switzerland without training or equipment. (Fortunately, we were sober that day. Going across the glacier was a rational teenage boy idea. The mind reels at what we might have thought of after a few beers.) My friend and I successfully crossed the glacier and reached solid ground before nightfall, proving once again the existence of Divine intervention, without which teenage boys would rarely live to see 21. |

Rhone Glacier

Rhone Glacier |

My father had a younger brother, Bill. After Harvard, Uncle Bill entered advertising on Madison Avenue, and eventually moved to New Canaan. My father followed his brother to Connecticut, settling in Farmington. Later in life, the two families moved to the Reserve, an enclave in Florida, where they lived for a quarter of a century. In my forties, I moved from California to Florida, where I met my wife, Rita, the ideal partner for my journey.

My mother, Penelope, was raised by a nanny until she was twelve, and never developed a strong connection with her mother. Perhaps to compensate for this, she showered me with love and affection in my early years. This left me with a deep-seated feeling of well-being, which not only elevated the quality of the rest of my life, but also was a great asset in reaching higher levels of awareness in meditation. The high point of my life was a six hour out of body experience I had during meditation at age 19 (which has been described at length elsewhere). Arriving in unknown states of higher consciousness one has not tasted in a hundred lifetimes is an adventure of the first order, and the more self-confidence one has, the farther one can go. I also had confidence that I could come up with a scientific explanation for this remarkable experience, and it only took me forty years of work to discover the Law of Conservation of Awareness.

|

| |

|

|

|